Lessons from the City of Lakes: Thoughts on Gender Imbalance in Cycling

This article is part of a series on alternative transportation and culture and is being cross-posted at the Asakura Robinson blog, where the author of this entry is employed.

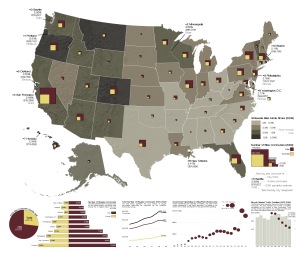

I recently stumbled across this post from a biking organization in Eugene, OR and found the graphic really interesting (I love a good infographic!). I’ve reposted it here, but click though to the original if you want to view it larger.

The article itself focuses on some of the big picture trends, the rise of commuting, the increased per capita safety of bicyclists, etc, but doesn’t take any time to analyze one of the most striking things in the graphic. There is a HUGE gender imbalance in biking today.

While this isn’t totally surprising, it is something that I can forget while I’m out riding in Boston or Houston. I feel as if I see plenty of women on bicycles, and, indeed there are a number of blogs, like Cycle Chic and its American copycats (there are links on the original site), that really celebrate women cyclists.

Image from Bike Fancy

I whipped out my iPhone and did some quick calculations based on the info in the graphic. Overall, 26.4% of bike commuters are female. This number is higher in most of the top 10 cycling cities. Here’s how they stack up in order.

- Minneapolis: 45.0%

- Portland: 39.1%

- Washington, DC: 37.6%

- Boston: 37.5%

- Philadelphia: 36.7%

- Oakland: 33.7%

- San Francisco: 31.4%

- Seattle: 30.2%

- New Orleans: 29.4%

- Honolulu: 21.7%

Incredibly, only my hometown of Minneapolis breaks the 40% line! Here are some of my thoughts on why.

For many, many years, bike advocacy and planning were dominated by the “vehicular cyclists,” or what many people call the Foresterites (as the philosophy was based largely on the book Effective Cycling by John Forester). The core of this theory is that cyclists are safest and traffic flows best when cyclists act exactly as traffic. The problem with this theory is that, male or female, it’s awfully scary getting out onto the street the first time as a vehicular cyclist. It takes time to adapt to riding with traffic and to understand how cars and bikes react to each other.

Anne Lusk, a researcher at Harvard who I’ve had the pleasure to have conversations with in the past, often said it bluntly: that sort of system is only really desirable for mostly white, 30’s and 40’s men on high-end road bikes. Most of that demographic who are going to cycle already do. As advocates and planners, we need to extend the livable streets mantra to cycling and work to create systems for cyclists of all ages, genders and abilities (for a good read on the history of cycling advocacy, check out Jeff Mapes’ Pedeling Revolution).

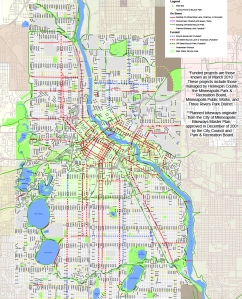

Minneapolis differs from many cities in that the core of its bike network is a series of off-road trails that has existed in the city for almost 100 years (the green lines on the map above, click for a bigger version). These routes are part of a historic parks plan that sought to preserve, protect and keep the city’s many lakes and waterways open to the public. By using them as a cyclist, it’s possible to get within about a mile of almost anywhere in the city without ever going on a street with cars.

This isn’t to say that a) Minneapolis hasn’t had to do any work to improve its bike network and increase cycling or b) that women don’t use on-street facilities. Minneapolis has done a ton of work to increase awareness of its network and has done an especially good job of creating new wayfinding signs that make getting around and moving back and forth between the on-street and off-street easier and rolling out a new, super-successful bike sharing program.

As to the second point, I believe that the off-street network creates opportunities for novice cyclists (of both sexes) to gain the confidence they need to feel safe biking anywhere in the city. While there are certainly some folks who both live and work on one of the greenways (Bike-Oriented Development has been one of the other major effects of this system in the last few years), most will have to use at least some on-street facilities at least some of the time. For biking to truly succeed in any city, we simply can’t focus on one demographic or gender… we must make biking work for everyone.

Excellent post. For women, the question for biking and many other activities is, “Am I safe?” This is especially true if the women are considering biking with children. Thanks for passing along the graphic, the article and your commentary!

Pingback: Encino Velodrome robbed; defending bike lanes from ill-considered online attacks « BikingInLA

How can I use this to site a paper that I am writing?

The author is Zakcq Lockrem. Then just use the blog title and the date originally published.

seems like advocacy/activism/general organizing should be emphasized as well…see for example http://greaseragmpls.wordpress.com/

Awesome point and great blog and organization! Any interest and writing up some of your thoughts on the subject for us?

Pingback: Bicycling’s gender gap: It’s the economy, stupid - Beezodog's Place : Beezodog's Place

Pingback: Economics of Bicycling « Walk Bike Costa Rica

Pingback: Mpls Park Board: Thanks! Oh, and I have a few questions. | Minneapolis Bicycle Coalition

Pingback: Plurale Tantum: A Look Back to Let The Conversations Continue! « plurale tantum

Pingback: A Pox On All The Edmonton Bicycle Commuters Society! | baconfat55

Pingback: Man Denied Entry Into Bike Shop Because... He's A Man. - The Libertarian Republic